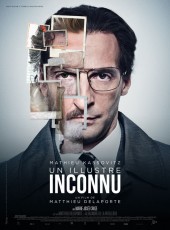

![]() Presentation by and discussion with director Matthieu Delaporte and co-screenwriter Alexandre de la Patellière

Presentation by and discussion with director Matthieu Delaporte and co-screenwriter Alexandre de la Patellière

Sébastien Nicolas, 42, is an ordinary real-estate agent who leads a solitary life, cloistered in the basement of his suburban house. Instead of striving for a better life, he prefers to duplicate that of others. Over the course of his encounters, he will turn himself into a specific character. Thus disguised, he will live the life of a total stranger in order to bring further meaning to his own. But one of these strangers, with a charged past, will push him over the line to a point of no return.

Cast & Crew

Director • Matthieu Delaporte

Screenwriters • Matthieu Delaporte, Alexandre de la Patellière

Producers • Alexandre De la Patellière, Dimitri Rassam

Starring :

Mathieu Kassovitz, Marie-Josée Croze, Eric Caravaca, Philippe Duclos, Olivier Rabourdin…

Choose a picture to see the filmography (source : IMDB)

![]()

Did you immediately decide to tell the story from the main character’s point of view?

The original idea was to write in the first person the story of someone who thinks he is nobody. People who suffer from this disorder – depersonalization – have inner world and live in constant self-analysis. They will easily tell you that they feel disconnected and lifted away. In fact, their vocabulary is close to a filmmaker’s lexicography. They speak in terms of characters, extras, dream sequences, etc. So I wanted to tell this story about a man who feels that he does not exist, that he is not part of the world, but who has this incredible talent for copying, since he cannot imagine, and as he goes along, looks for himself in other people. I wanted to use story-telling and fiction to say something about that quest for identity which is of an intimate and psychoanalytic nature.

The protagonist behaves like a serial killer: obsessional, meticulous, precise. However, he never kills anyone.

One of the suggestions I made to Mathieu Kassovitz for the part was to consider him as a serial killer who never acts on his impulses. I wanted to use all the trappings of the serial killer, though the story is about a man who could not harm a fly. He is much more suited to hurting himself than someone else – and he is actually afraid to break away from his family. Very often people who suffer from depersonalization disorder have spent so much time learning what they must do that they no longer know what they want to do. They know how to make others happy – which makes them perfect social beings – but they have forgotten all about their own desires. When you think about it, that is the whole story of writers like Romain Gary and Fernando Pessoa, who were big sources of inspiration for our film. Gary, for example, created an alter-ego in order to free himself from certain constraints. He was a writer, an ambassador like his mother always dreamed – and he made up an alias in order to become himself. Pessoa created heteronyms in order to defer his feeling of inexistence and disappearance. What I like about Sébastien Nicolas is that his impostrous nature is, paradoxically, a kind of search for the genuine.

Could Sébastien Nicolas also be a metaphor for the writer or the filmmaker who literally feeds on other people in order to imagine a story or a destiny for his characters?

Absolutely. I have done a lot of reading about writers and their taste for alter-egos. For the protagonist there is also the metaphor of the actor who does not want to leave his role because he only feels alive when he is donning a character. What I find interesting about this whole usurpation theme is that it goes to the heart of what fiction is all about. And people who suffer from depersonalization disorder want their fiction – their private “novel” – to take the place of reality.

In the film, fiction actually triumphs over reality.

Yes, it is a real victory for mystification. I had actually written an off-screen narrative – which I cut in the end – where he says, “I do not counterfeit, I pro-feit.” Sébastien is not someone to use someone else’s identity for his own benefit – he uses the leftover portion. He takes the life of a man who does not want it anymore. On the one side you have this great but desperate musician who comes face to face with himself and no longer wants any part of it. On the other side you have Sébastien Nicolas who feels like he is no one at all and who wants to take on a life. The imposture only works if it satisfies a desire – you cannot take someone else’s life unless his entourage wants to believe. Then events catch up to Sébastien Nicolas. Because you cannot change your life without doing damage and hurting other people.

The film is also about family descendance, or absence of descent in the case of Kassovitz’ character, who is terrifyingly alone.

The father figure is looked at from several different aspects. The absent father, the religious father in whom Sébastien confides, and the father he becomes for himself, because in a way he sires himself. In doing that, he also becomes the father to a child who is in need of a parental figure. In accepting this new identity, he becomes his own father. Is it the child’s love that gets him over the hump or is it immersing himself in another identity which allows him to become a father? For me, those two things are inextricably intertwined. I think he suddenly feels he can exist, and he never imagined that was possible. So he crosses the Rubicon and deals with all the consequences.

Why did you choose a violinist?

I was looking for a profession that you cannot continue if you lose part of your body. Henri de Montalte is a passionate being, inhabited by his art, who lives for his music, so he loses his reason to live. The violin is so precise that if you lose two fingers, you can no longer play. It is also an instrument that is brought to life by the musician – the tiniest note on a violin is unique to its player. Only a violinist can really say he can no longer practice his art. The musician places the music between himself and the world, to protect himself. When you take away that shield, he is naked and exposed to other people’s eyes. And Sébastien Nicolas, who had been naked because he has no imaginary life, takes this shield he finds along his way.

Mathieu Kassovitz plays the parts of most characters. Was it a challenge?

I met with several actors because this is an extremely difficult part. But after reading 40 pages of the script Mathieu called the producer to say that if the next 40 pages were of the same quality he would do the film. Now I think that the film would not be what it is without him and sometimes I get dizzy spells when I realize he might not have come along! With Mathieu, things were very simple – he just immediately understood what I wanted. If an actor is going to give you his best, he has to open up and go looking for that fragile part of himself. That is the role of the director. We got along very well, in a very professional way, with mutual respect for each other’s range of prerogatives. As soon as he got to the set and saw where the camera was, he knew exactly what to do and how to position himself. He has an extraordinary imagination, sensitivity and sense of modesty.

It was a particularly painful shoot for him…

He survived 13 weeks with four hours of make-up a day! At the beginning, I did not realize how much of a physical challenge that would become for him. Luckily, Mathieu is in great shape and quite athletic. I think another actor would have been exhausted by the end of the shoot. But Mathieu was a rock – and that is not necessarily obvious. He gives off this very fragile quality. And in addition to that, he is inventive every time out, avoiding the easy solutions. That makes it possible for anyone to see himself in that character – he has the ability to play an everyman and at the same time he can play other people without aping them. It never feels forced or made up.

Was it always the plan to have him play both roles?

We had a lot of discussions about that and we conducted a few different tests. What was sort of complicated was that, if we did not have control of both the original and the copy, it meant that Mathieu would be copying a fictional character, in other words, playing the role of someone who, in turn, is playing a role. That Russian doll effect would have been unnecessarily complex. In reality, the violinist is his own perfect target. After having copied other characters in a satisfactory but imperfect manner, he finds his “masterpiece” in Henri de Montalte.

What can you tell us about your directorial technique?

Everything is seen through the eyes of Sébastien Nicolas. Aside from the pre-title sequence, we watch him as he himself watches others. The audience has this clinical vision of the character and, little by little, comes around to his point of view, sharing his emotions, experiencing empathy for him. As far as the filming is concerned, at the start of the film everything is in studied shots and Sébastien is always standing around the edges of the frame, as if he himself were socially conventional. Everything about him is impeccable – almost too much so – and that is reflected in a rather cold, controlled and geometric frame. Then later, when Sébastien begins to move and feel, the camera starts to move, there are blurs, as if the direction suddenly has become more organic. Our head camera operator David Ungaro and I tried a bunch of cameras before we found the one we thought was best for the idea we had of the film.

Press Kit “Un illustre inconnu”

English ~ 14 pages ~ 1,5 Mo ~ pdf

Press Kit “Un illustre inconnu”

French ~ 10 pages ~ 705 Ko ~ pdf