![]() Presentation by and discussion with director & screenwriter Stéphanie Gillard

Presentation by and discussion with director & screenwriter Stéphanie Gillard

• Special screening honored by the presence of director, producer & actress Georgina Lightning (Maskwacis/Plains/Cree), director & producer Chris Eyre (Cheyenne/Arapaho) and actor & stuntman George Aguilar (Apache/Yaqui) and by members of the Eleven Native American Tribes of Virginia. •

Each winter, a troop of Lakota Sioux crosses the wide plains of Dakota on horseback to commemorate the massacre of their ancestors at Wounded Knee. While going through territories which no longer belong to them, the eldest attempt to pass on their culture, or what is left of it, to the youngest. A journey through time, the 300-mile trip rebuilds a lost identity and makes America confront its own history.

Cast & Crew

Director / Screenwriter • Stéphanie Gillard

Director of Photography • Martin de Chabaneix

Music Composer • Vincent Bourre

Producers • Julie Gayet and Nadia Turincev

The Cultural Service of the French Embassy:

The Cultural Service of the French Embassy:

Supporting Contribution for Documentary Screenings

In association with the new Pocahontas Reframed Film Festival: Native American Storytellers (November 17-19, 2017) supported by American Evolution 2019 Commemoration, Virginia Film Office, Francis Ford Coppola and the Eleven Native American Tribes of Virginia.

Your movie has a real political dimension.

This film is about the ride itself, but also about the event that the riders commemorate: Wounded Knee, the last massacre that ultimately sealed the end of the Indian wars. It is not just any event and the film is very political because of this historical context. The film helps us understand how history shapes the present. On this journey, the riders tell us about their lives and about what happened on the same route 125 years ago. They recount what the United States government has done to their nation and to their people for generations: evangelism, acculturation, suppression of language, as well as constant and insidious theft of land.

During the 15 days of the ride, the participants raise their heads high and are not in the miserable state in which they are so often depicted. In facing cold, blizzards, snow, hunger, and in the eyes of others, they embody courage, solidarity and dignity. Galloping across the Great Plains, they become, for two weeks, if not warriors, then at least members of a nation that was once free. The riders come together around their history as they declare the importance of memory, transmitting it, along with their values, to the next generation. This ride is a path to become themselves, to become Lakota again.

The journey follows a trail of tears, but becomes a joyful experience for the riders, and makes a compelling and uplifting story. The film is important for viewers around the world. It shows a great example of humanity, generosity, courage and wisdom, at a time when those values are so often forgotten around the world.

How did you get to know about the Sioux memorial ride which takes place every year in December?

I have long been captivated with Jim Harrison’s books, I began to read all his books. That is how I came across a photography book for which he had written the preface. One of them depicted Sioux Riders braving blizzards on horseback, riding down a snow covered hill, their faces covered with iced-over bandanas and ski masks. In another one, the riders held feathered staffs high in the air as they rode along an icy road, followed by a long line of old Chevys. Another one of them reminded me of a photo by Edward Curtis.

I found these pictures really moving, as if the US history was springing up on the side of an interstate road, in a country where you are always told there is none. It was miles away from the usual “clichés” I was used to hear about Native Americans nowadays. I saw pride, I saw people fighting for their culture, not even in a political sense, but above all for themselves.

I immediately thought that I wanted to meet the people who were doing that and searched everywhere for a way to get in touch with them. Even though these photos dated from 20 years ago, I knew that this journey was still happening each year. Eventually, I found a phone number on Facebook. When I called, a woman told me that if I was interested, I only had to come.

How did you manage to be accepted by the Sioux people?

As I wanted to be part of it, I went on the Ride for the first time in December 2009. I was a bit shy, I knew I was a foreigner to everybody, but I became more familiar with the participants day after day. I slept in the same gyms, I helped with the horses and meals whenever possible and I listened to them, laughed with them. I really wanted to live the adventure with them. Every day, they offered to let me ride a horse, but I didn’t feel legitimate enough for that commemoration. In fact, I felt more like a representation of the enemy. They reassured me, saying that the ride was all part of the process of forgiving and remembering.

Nevertheless, I preferred to jump in a different pick-up truck every day and speak with the support crew. In Throughout the process, I discovered their stories, their points of view, the paths they had taken and why they chose to go on this journey.

One day, a rider told me that he had found a horse, and that I should saddle it and take the reins.

What followed was seven hours straight on a trail with -17°F temperatures and sleeping in a car at the Big Foot Pass, despite the snow seeping inside. Christmas was on the following day with an actual Blizzard. We had to wait for hours in the wind, holding the horses so that they do not run away. Finally, after feeling like we had survived a bitter-cold version of hell, we found our paradise at a tiny gas station. In this case, paradise consisted of a liter of java, a pack of chips and cigarettes.

I think the Ride stole my heart that day and now I cannot imagine being somewhere else for Christmas.

I had an idea of the severity of this journey when I undertook it, but it was well beyond what I imagined.

In February, I went there for a second time. I toured three reservations in an effort to see again everyone I met on the Ride. This second meeting was even more powerful. They were surprised and happy to see me again, especially the children. People usually do not come back for a visit. Many on the reservations feel that the world is not interested in them. They also were excited that I brought them some of the photos I had taken, as most of the media come and leave without showing any of what they filmed or photographed.

I did the Ride again in December 2010 and came back over the summer 2011 to spend more time with the Lakota people and learned more about their daily routines and lives. We have kept in touch since then . . . They have become my second family.

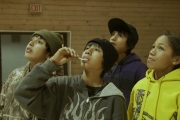

In your film, children seem to have an important place. Can you tell us why that is?

I was particularly inspired by the Lakota youth I met during my visits: the candid smile of Jesse and his love for horses, Wolf’s laugh when he sings in the heart of the night, Carla’s doubts about her future, T.C.’s seriousness as he considers joining the army, Chang who was looking for me each time he wanted to play a game, and Ramey who always invited me to dance – I spent magical moments with all of these young people. Throughout the Ride, we laughed, cried, got hungry and cold together. I heard their voices, their doubts and their stories. Though they are so young, they often astonished me with their maturity, especially after a childhood where they were given little hope for a bright future. I asked myself how can one live with this strange duality: to be American and Sioux at the same time, to keep that question silent while often not knowing the answer.

Press Kit “The Ride”

English ~ 9 pages ~ 1,8 Mo ~ pdf

Press Kit “The Ride”

French ~ 9 pages ~ 6,2 Mo ~ pdf